A Time of National Reckoning

or two years, LaDarius Price sounded the alarm concerning the health disparities plaguing his Chattanooga, Tennessee, community. In addition to personal observations, anecdotal information and national statistics, he finally had the local numbers to prove it.

One year into Price’s campaign for healthier living within the African American community, Hamilton County released a 2019 community health profile revealing the magnitude of the racial divide. According to the report titled “Picture of Our Health,” compared to the white population, black residents were:

- 35 percent more likely to die from stroke

- 30 percent more likely to die from heart disease

- 23 percent more likely to die from breast cancer

- Four times as likely to die from hypertension

- Two times as likely to die from kidney disease

Fueled by such startling statistics, Price poured his heart and soul into his position as community outreach director for Cempa Community Care, a Chattanooga nonprofit that provides affordable, comprehensive services to the community. Price launched a “Cempa Workout Jam,” organizing free neighborhood workout sessions, complete with an exercise instructor, DJ and healthy snacks. He started a faith-based health and wellness council, resulting in a healthy competition between congregations to see who could lose the most weight and achieve the best blood pressure numbers. He took his campaign to public schools and HBCUs, educating young people about their sexual health.

Price said he seemed to be making progress as more and more people began attending events and adopting healthier lifestyles. But that was before COVID-19 hit the community like a sledgehammer, wreaking havoc on minority neighborhoods, where black and Hispanic residents died at significantly higher rates than those in the white community.

Photo by LaDarius Price

From left to right: Community health advocates LaDarius Price and Chris Ramsey provide COVID-19 testing in underserved Chattanooga, Tennessee, communities in 2020. Ramsey died from the deadly virus in January of 2021.

As COVID spread rapidly, Price and other health advocates scrambled desperately to get people tested and educated about the global health threat. But the death toll continued to climb. And in an ironic twist of events, Price lost his mentor and comrade, Chris Ramsey – a beloved African American health enthusiast who helped lead many of the local initiatives – to the deadly virus.

“The light was already shining on the disparities that were there,” Price said, reflecting on the early days of the pandemic. “What COVID did was take it from being a flashlight to football stadium lights; so, it was broadcasted for the world to see, when COVID hit.

“Some people died because they already had underlying health issues. For others that were fortunate enough not to die and transition, they are now, even today, seeing the lingering effects of COVID,” he continued. “I often say, ‘When white people catch a cold, black people catch pneumonia. And what I mean by that is: If you thought it was bad for our Caucasian counterparts during that time, just imagine how bad it was for us as a community.”

Chattanooga is just one example. Throughout the United States, many minority communities remain devastated by the effects of the global pandemic, which ravaged vulnerable populations due to pre-existing conditions, insufficient early testing among minority populations, and poor public health policies, according to national experts and local community leaders. Nationally, COVID-19 ushered in a period of reckoning over the health disparities between people of different races and socioeconomic backgrounds. What already had been evident in cities such as Chattanooga became even more visible and impossible to ignore.

David Williams, chair of the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said a gap in life expectancy existed between African Americans and white Americans before the pandemic. Williams said in 2020, the average African American lived a six-year shorter life expectancy than the average white person. The gap is only two years less than the eight-year life expectancy gap between the two races in 1950, he explained. Though white and black Americans have experienced increases in life expectancies over time, the gap remains persistent and has even widened since COVID.

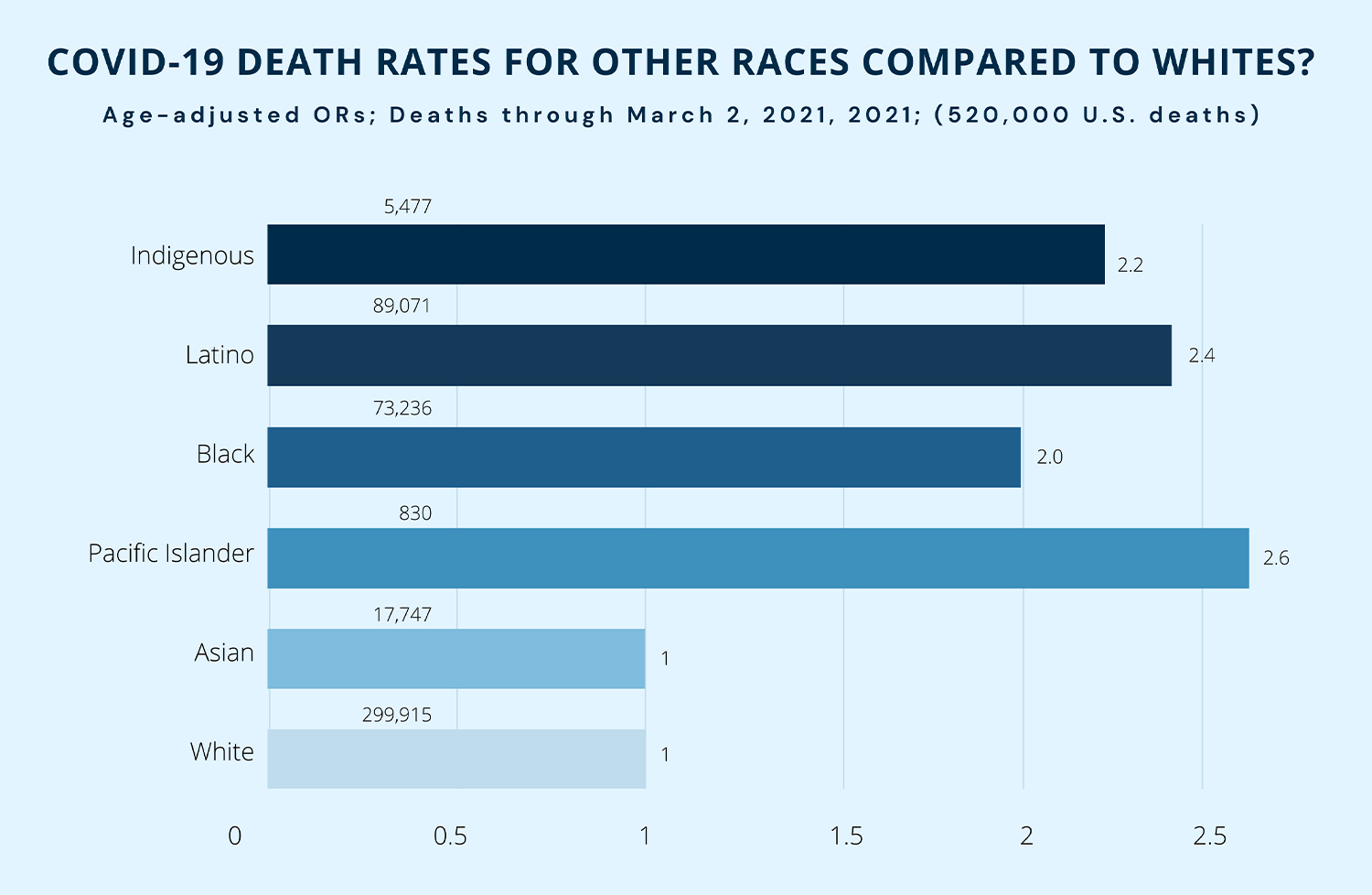

“For the first half million deaths of the pandemic, all disadvantaged populations of color –Native Hawaiians/ Pacific islanders, Native Americans, Latinos and African Americans all had age-adjusted death rates for COVID-19 that were at least twice that of whites in the United States,” said Williams, who also serves as a professor of African American studies and sociology at Harvard.

“And as a result of COVID, life expectancy in the United States declined,” he added. “ … We have not seen such a decline as has occurred from 2019 to 2020 since 1944, and it has widened the gaps between blacks and whites and other groups.”

For example, the life expectancies for Hispanic and African American males declined by least three years from 2019 to 2020, Williams further explained. The life expectancies for Hispanic and African American females declined by more than two years, while the life expectancies for white males and females by more than one year.

Photo by LaDarius Price

From left to right: Chris Ramsey and LaDarius Price, Chattanooga community health advocates, promote a Health Fair in 202 just before SOVID-19 hit the community.

“What is happening in the United States is that African Americans, compared to whites, are getting all of the major chronic diseases, not just at higher rates, but at younger ages, so that we are becoming more vulnerable,” Williams said. “Researchers are using the term ‘accelerated aging,’ or ‘biological weathering,’ or ‘premature aging’ to capture what’s happening to African Americans.”

When identifying the causes for such disparities, public health experts refer to the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), which include:

- Economic Stability

- Education Access and Quality

- Health Care Access and Quality

- Neighborhood and Built Environment

- Social and Community Context

The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services used, as an example, people living in communities without access to grocery stores with healthy food items.

To address the problem, the agency has developed a Healthy People 2030 program to identify “public health priorities to help individuals, organizations, and communities across the United States improve health and well-being,” according to the information posted on its website.

Despite some setbacks due to COVID-19, Price said he would continue his initiatives in Chattanooga through his work at CEMPA Community Care. Furthermore, he encourages others to join the fight.

“I just want to continue this work and make people aware of what’s going on,” he said, “and how we can truly move the needle as it relates to health disparities.”

ALVA JAMES-JOHNSON is an associate professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at Southern Adventist University and an award-winning journalist who has worked for several newspapers across the country.