You’ve heard some of these before:

- They are too expensive!

- Their customer service is horrendous.

- Their storefront looks homespun.

- Their quality is subpar.

- They are inconsistent.

I could go on, but you get my point. Before I begin debunking these myths, you must know that this conversation goes deeper than the “not all black businesses” narrative, as well as the “we are not monolithic” point. Black-owned businesses seem to get the short end of the business stick. In order to see the full picture while avoiding the pitfalls that accompany trying to explain fallacies associated with the black community, we must start at the macro level.

When starting a business, the most important element that leads to success is a strong foundation. Ever heard of the Bible story about building on the rock vs. on the sand? We should all be able to agree that a rock foundation is ideal, but what if you only have access to sand? This reality is more common than you think, and it is not racially exclusive.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 20 percent of U.S. small businesses fail within the first year. Four years later, nearly 50 percent of that number have waned. Finally, 10 years later, about 33 percent of businesses have stayed afloat. These sobering stats do not contemplate the probability for weathering a global pandemic and other external factors.

Now for a moment, let’s consider what may have caused so many small businesses to fail. Also consider, how many of these small business owners either completely relied on their business for personal survival, or had to take on a job just to keep the business afloat. LendingClub.com asked more than 2,500 current and aspiring entrepreneurs about their most common problems. The results are interesting:

- Access to Capital/Limited Cashflow

- Marketing/ Advertising

- Time Management

- Performing Administrative Work

- Hiring and Retaining Top Talent

- Providing and Managing Benefits

- Navigating State/Federal/Government Regulations

Lets address the first item, which affects all the others. Without access to capital, along with limited cashflow, the small business owner has significantly fewer options, and that makes it a pain to successfully address all the other problems. The consensus has been that “new startups usually have limited customers and many competitors.” This means that there is a high risk that the start-up may fail. If that happens, the startup might not be able to repay the investment.

Did you catch that? The data was pulled from a small business credit survey. That means that creditworthiness was not only a major factor in loan approval rates, but may even be the primary measuring tool used by banks for access to capital.

Black-on-black crime implies that intra-racial crime is exclusive to the black community however, studies show that most crime is intra-racial due to proximity. I recently read that “82.4 percent of white people are killed by white people,” yet there’s no such thing as “white on white crime.”

Unfortunately, the perpetuation of these myths makes the odds much harder for black-owned businesses to succeed. Combine that with the obstacles I mentioned above, and you have created a perfect storm of stumbling blocks. But still, we rise.

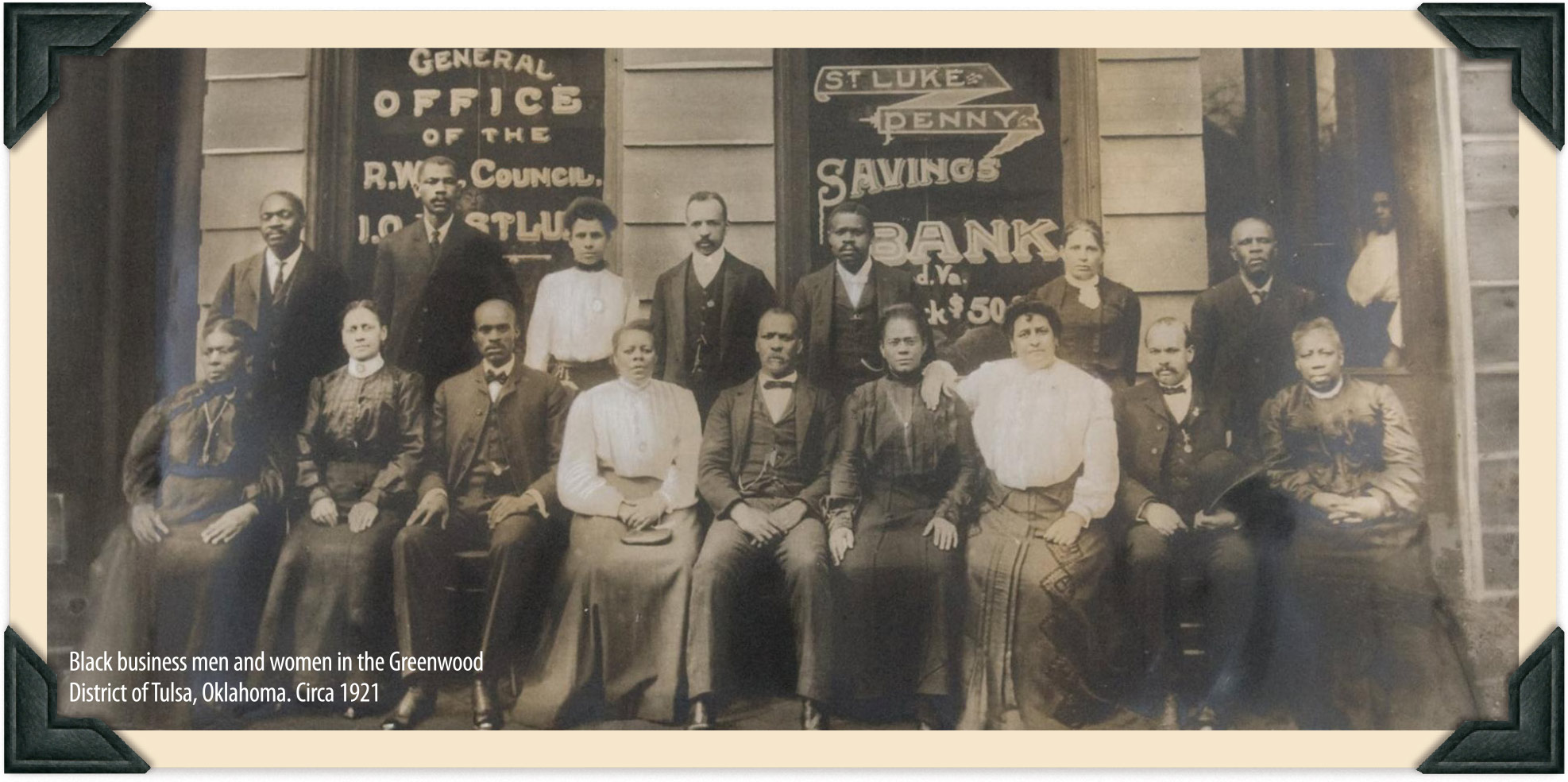

In the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma, the community of black businesses flourished. The success found within Black Wall Street was due to continuous community support, not just through patronage, but through access to support systems and mentorship that enhanced the ecosystem.

Although segregation and Jim Crow laws were meant to have a negative impact on the community, those barriers contributed to the enhancement of Greenwood’s already strong infrastructure.

Make informed choices and think critically about where you spend. Next time you shop, consider whether your belief, or negative experience, is exclusive to black-owned businesses; or do these issues plague small businesses, in general.