Real-Time School of Love and Justice

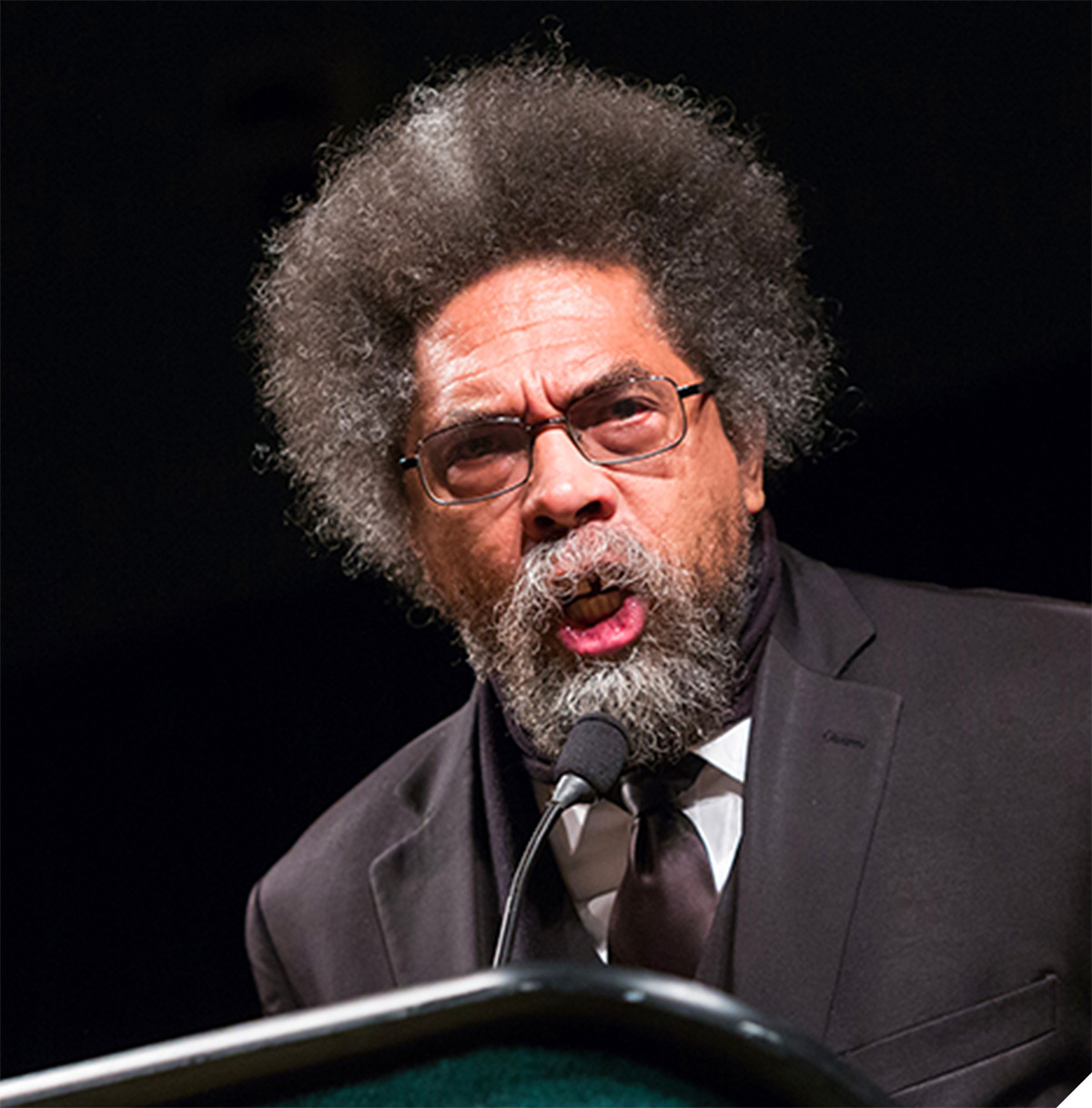

An acclaimed American intellectual, philosopher, author, speaker, Ivy League graduate, and professor, West’s perspective has saturated the social justice lexicon. From his seminal 1993 Race Matters to his 2014 Black Prophetic Fire, the books in between, spoken word albums, and even acting—in the futuristic, dystopian, “The Matrix” enterprise—one can always recognize his voice. While “Councilor West” didn’t appear in the latest Matrix, his new Masterclass, launched last November, covers philosophy, compassion, and what it means to be human.

West’s employs the black, prophetic tradition—one of faith in the face of struggle—as a means of interpretation and interaction. Our recent interview with West, proved to be yet another session in his prophetic paideia, (an education that forms the soul or, as West would call it, a “deep education that informs and transforms us”) where he issued the unflinching call to love and justice.

’ve always understood myself as one of the most blessed human beings in the history of the species because I was a second son of Irene and Clifton West, and was shaped and molded by Shiloh Baptist Church. Those are the two most fundamental pillars in my own sense of who I am. And that goes far beyond any kind of worldly achievement, earthly success or education, and so forth, because it gave me a gift of love and a gift of grace that rooted me in concrete experiences of what love really is. And, then a lens through which to view the world which is always the lens of the cross.”

“So from the very beginning, I’ve always tried to be in the world but not of it. Not to be conformed to the world, but transformed by a grace, a gift that I had no control over, that is so much grander than me, and that could use me, given the cracked vessel that I am—to learn how to love my crooked neighbor with my crooked heart—as it were.”

The scene in Charlottesville, Virginia 2017, staged a perfect opportunity to illustrate this intersection of love and grace, and justice. You remember Charlottesville. The major alt-right and white supremacist rally attracted young white men in t-shirts and dockers carrying tiki-torches. There were bikers, and rabid social media personalities, the Klan, and neo-Nazis. It was there that James Fields, a 22-year-old neo-Nazi from Ohio, rammed his car into a crowd of anti-supremacist protesters. He plowed through a sea of humanity, killing a 32 year-old paralegal, Heather Heyer.

Cornel West was protesting in Charlottesville, too. The afro and beard, unmistakable. The black suit, white shirt, dress shoes, serious. He was on the anti-racist frontline, amid a hail of cussin’ and epithets, when a brother in a gas mask approached him from behind and was mad at him.

“’The thing I can’t stand is you always call everybody, ’Brother,’ Brother West.’” His irritation was very apparent. “’That just burns me up,’ he said. ’Why you say that?’”

West sets the scene: the two men squared off in front of each other, two microcosms on the same side of justice. “He got all his people, and he’s saying this through a gas mask—with guns that got ammunition in them—and we’re sitting there, singing ’This Little Light of Mine,’ and just unarmed.”

That’s when, of all times, the non sequitur of love, grace, and justice emerged in the conversation: “I whispered in the brother’s ear. I said, ’I just want you to know that Jesus loves you the way Jesus loves me. I don’t have any special access to Jesus.’ I said ’for you, my brother, you just choose to be a gangster. I was a gangster once, too. Well, I got redeemed.’”

The man’s friends pulled him away, while West called out to them. “’We just need to know what the witness is. He just needs to know what the tradition is. He needs to know what the legacy is. He needs to know what it really means to be—or attempt to be—a follower of Jesus.”

hen his parents presented him as an infant to the church for a blessing, the choir rang out “Jesus, Be a Fence,” and the whole place sensed a calling on little “Ronnie” West. However, he acted the part of a little gangster before he accepted Jesus. He staged his own protest of the pledge of allegiance, refusing to stand and recite it, which led to a physical tussle with his teacher. He beat up the bigger bullies and dispersed their resources among the kids who had little to eat. His baptism, however, sealed his conviction that He would walk with Jesus, always, and is where he attributes the unflinching need and ability to speak truth to power.

As a student at Harvard, West clashed with administration over Black studies curricula and divestment in the Vietnam War. Years later, when Dr. West was a tenured professor there, he left in 2002 “after a public fight with the university’s president,” according to The Washington Post. Last summer, West again left Harvard where he was a respected, but this time a non-tenured professor in the Harvard Divinity School. On the way out he attached his resignation letter to a Tweet, citing “spiritual rot” as a main reason for his departure.

West’s protest surfaced in a summer of discontent. We watched as conservative opponents blocked the recommendation of tenure for Pulitzer Prize-winning Nicole Hannah-Jones. Underlying their opposition was her groundbreaking work for The New York Times’ “ The 1619 Project.” The truth she told traced the legacy of slavery, and has become a target for many who oppose a critical look at the nation’s racial and racist history. Also last summer, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary pulled the plug on its only black theology professor, Emmett Price, III, citing budget cuts. His supporters were stunned at the insensitive timing.

Before that, West’s famous critiques of the Obama administration led to a chilly, social winter in the black community. One article, curiously titled “Everyone Hates Cornel West— How Cornel West Went from Liberal Media Darling to Pariah,” argued West’s fading effectiveness in inspiring conviction, and thus votes, before the 2016 presidential election and painful path of rejection. “[T]he same liberal intelligentsia that once championed West has not only thrown him overboard, but seems to delight in making a public spectacle of their scorn for a man they claim is little more than ’embittered’ after being ’spurned’ by the first black president.” (jacobinmag.com)

“I whispered in the brother’s ear. I said, ‘I just want you to know that Jesus loves you the way Jesus loves me.”

“The centrality of Wall Street power, US military policies, and the complex dynamics of class, gender, and sexuality in black America is too narrow and dangerously misleading. So it is with Ta-Nehisi Coates’ worldview.” (“Cornel West’s Attacks on Ta-Nihisi Coates Explained,” by German Lopez. Vox.com) Rather than participate in a public feud as a black intellectual, Coates backed away. His work is generally limited to topics in his central focus or expertise, he said in an interview. And, he certainly didn’t want his legacy to include a fight with West. Both men ended up stepping away from Twitter for a while.

Must being so principled lead to this high-stakes public sacrifice? High-profile loneliness? Does a prophet have room for strategy, negotiation, maybe compromise? Could any of this had gone differently? West welcomed the question. It goes to the heart of who he is.

“I’m just trying to be true to who I am. . . . I wear Harvard like a loose garment,” West explained. “I wear every earthly institution like a loose garment. It’s just the earthly vessel that passes away. I got a connection to something that’s grander and greater than me. That gives me all that I need, and more.”

He registered his critical independence with candidate Barack Obama, early, when the President called on him for campaign support.

“I said, ’Brother, I look at the world through the lens of the cross. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others, for me, exemplify so much of what it is to look at that world through the cross. I just want to know what is the relation between what you plan to do and the legacy of the cross and Martin King?’ We talked for four hours.”

“That’s why I had to be critical of Obama when he bailed Wall Street out rather than homeowners. He’s siding with the money changers. Somewhere I read Jesus ran the money changers out of the temple. That was the largest edifice west of Rome, east of Rome; I should say the largest edifice, hundreds of troops protecting that temple, bankers on the side, intellectuals rationalizing the bankers. Jesus goes in with his ragtag group . . . and He runs out the money changers. What He’s not saying is: ’I hate the rich.’ He says, ’I hate greed. I hate injustice. I love everybody. And I love the poor.’ The folk are exploiting the poor.”

he art of civil and impassioned discourse has devolved in the decade and a half of social media democratization and empowerment. We would like to think inspirational discourse pulls aggrieved parties together and effects genuine understanding. West is a vocal proponent of such collaboration and breaking of bread with, even “enemies.” Yet, his own fierce independence caused him to resign and then tweet about the “spiritual rot” at Harvard. Is there ever a sweet spot in the prophetic quest for justice? Where is the balance?

“Anytime you talk about justice, it’s going to be an inadequate discourse, unless it’s rooted in something deeper than justice. Reinhold Niebuhr used to say, ’any justice that’s only justice will soon degenerate into something less than justice.’”

“And this is where the cross comes in. You’ve got to have love. Love is deeper than justice. Justice has to do with an institutional arrangement of fairness. Love has to do with a smile, a grin, a touch of friendship, of fellowship, and an embrace of the institutional arrangement of fairness.”

“Love trumps justice, always,” said West.

“What is distinctive about those who follow through on Jesus of Nazareth, on Jesus Christ, is, this is not no lifestyle choice! This is a calling. It’s a long-distance run. It’s being a marathoner for the Master, for Jesus. And so in that sense, the question of deep love spills over into struggles for justice.”

ove and justice. When he left Harvard, West didn’t like the way his class and program were being considered and challenged. On top of that, however, his complaint extended to a very personal and intimate critique: where were his colleagues, the administration, when his 97-year-old mother died? It was an opportunity for them to show love.

“Yeah, that’s true,” West said.

As far has he is concerned, institutions who care about justice would add to their success when individuals in the institution work toward meaningful, loving, engagement.

“You can’t just be, you know, Martin Luther King Jr.—full of fire for justice on three days a week—and four days a week you’re not treating the people in a loving, tender, gentle, sweet way. Because love is manifest[ed] in a number of different ways. The great Soren Kierkegaard classic on works of love said love is many things, many manifestations, many forms. And, justice is just one. Just one.”

“Now, just as black folk, you know, we come from people who have been chronically hated for 400 years, but teach the world so much about love because at our best we’ve been a sweet and tender people.”

“We’ve been soulful. Soul is the sharing of a soothing sweetness against the backdrop of catastrophe. You hear it in the voice of David Ruffin. You hear it in the voice of Aretha. You hear it in the sounds of a Coltrane, or Mary Lou Williams, or Sarah Vaughn.”

“That’s not skin pigmentation, at all. That’s spiritual formation. That’s artistic cultivation. That’s a soul and a spirit, even though it was hated, terrorized and traumatized. It keeps dishing out joy.”

is the stubborn decision to live in joy, on the Word of Jesus Christ, that is precisely up for question now. Black people in the United States, in particular, have cooled on the idea of the traditional Christian church, as have others, though not at the same rate. For those who leave, they cite, among other things, the association with white supremacist teachings or interpretation of the biblical text, or social and political ideology that lacks real teeth in matters of social justice. Even as we feel increasingly embattled and endangered, systemically and interpersonally, the choice to be made pivots on how we want to leave the world.

“I see these neo-Nazis and fascists. It’s the same manifestation of the old ’hounds of hell’ that the great Howard Thurman talked about: greed and hatred and manipulating fear, and trying to demonize and dominate others. And it’s inside of all of us, “West said.” We got hatred. We got greed. We wrestle with hypocrisy. We choose to follow Jesus. We choose the love path. We choose the love train…. If you give up on the power of grace and you give up on the lens of the cross, then you become just part of the gangster-ized terrain like everybody else.”