ore than twenty years ago, my beginner’s swimming class just finished learning how to glide in the water using a technique known as “the superman”– where you put your head underwater, stretch out your hands, and push off the wall of the pool. Sitting on the poolside at six years old, there was one problem. I was too afraid to put my head in the water. Unfortunately for me, that was not the scariest lesson of the day.

The thought of jumping off the diving board gave me great stress, anxiety, and fear. As my toes inched toward the edge of the board, I froze. One of the lifeguards told me there is only one way off the board and that’s jumping into the water. When I refused the lifeguard gently tossed me in. That was one of the worst, most embarrassing days of my life.

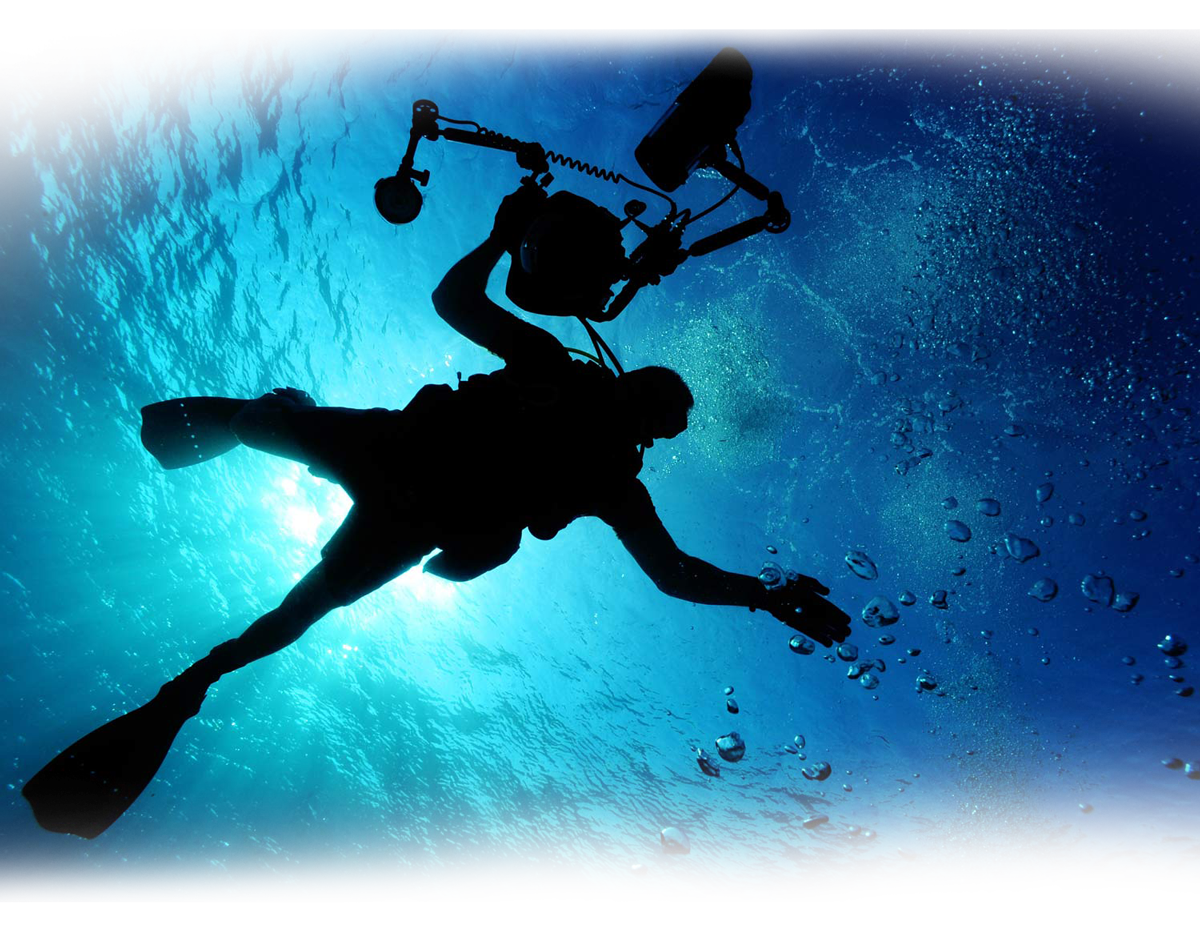

I trained under Diving With a Purpose (DWP), a group of mostly African American scuba divers dedicated to the preservation of sunken African artifacts and slave ships. They work in partnership with the Smithsonian Institute, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Parks Service, and the George Washington University Slave Wrecks Projects. During this particular trip, I learned to navigate the ocean floor as an archaeological surveyor scuba diver. We spent hours in the pool swimming laps, treading water for 20-30 minutes, taking off and putting on gear underwater, and learning how to map and draw objects on the ocean floor.

As I geared up to enter the depths of the ocean, I couldn’t help but think about that little kid who was scared to death to jump in the deep end. He had no idea the life he’d end up pursuing. I also thought about the enslaved men, women, and children from Africa who were violently thrown off ships into the Atlantic Ocean because they were sick, or participated in an uprising against their captors. I am training to have the sacred honor of preserving the rawest form of the Middle Passage, the engine of the African Diaspora.

A brother at church noticed my interest in swimming and introduced me to a scuba diving program. Through the program, I received most of my scuba certifications before graduating high school and even before getting my driver’s license. After obtaining my bachelor’s degree in history from Oakwood University, I earned my master’s degree in history from Howard University under the tutelage of Dr. Emory Tolbert. It was during my time at Howard University that I was approached to by a fellow colleague to be a part of a historic project to dive for sunken slave ships through DWP.

I feel most free when I’m in the ocean. The calm silence of the sea with the sound of the waves rippling meters above me is something that I crave. I can hear the bubbles leaving my regulator as I breathe. I hear my heart beat slowly as my mind relaxes with the current. It feels as if I’m flying as I replicate the effortless movements of the fish around me.

God has made the ocean a dynamic ecosystem full of life and natural treasures. As man used it for travel and trade 400 years ago, it became the gravesite where our ancestors were forced to their deaths. Many ships were destroyed by the ocean’s wrath, however, the ocean left just enough as a reminder of what evils sin can do to God’s creations.

God has turned a kid who was scared to put his head in the water into a strong swimmer who is a preserver of our fallen ancestors at sea. It is nothing but the grace of God that has taken me this far, but I know He is going to take me to places I’ve never dreamed about heading—one dive at a time.